The Seven Strategic Failures That Will End Khamenei’s Rule

Khamenei’s Irreversible Mistakes

As protests increase across Iran, the Islamic Republic now faces structural pressures it is fundamentally ill-equipped to manage. I genuinely think that Khamenei will not survive them. In fact, these are not temporary shocks or policy errors that can be corrected with reform or repression, they are essentially systemic constraints that the regime lacks the capacity to resolve. It’s a subtle difference, but I believe it matters.

Khamenei himself bears direct responsibility for accelerating this crisis. As Supreme Leader, as the embodiment of the Guardianship of the Jurist, and as the final arbiter of strategic decisions, he made a series of choices that cannot be reversed. This is, I should say, a perfect case study of how revolutionary theocracies collapse from within.

This piece identifies seven strategic errors that rendered the regime’s condition irreversible. Taken together, they mark the beginning of the end. I do not believe he will remain in power for long. It is a bold prediction—but all indicators are flashing red.

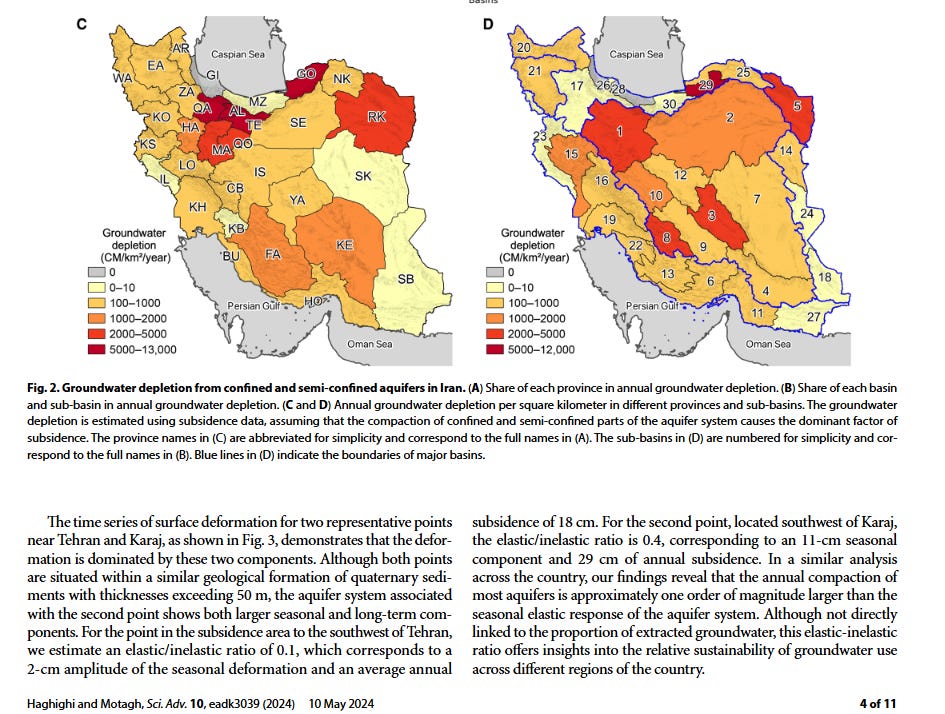

1.Water Management Incompetence

Water management competence is non-negotiable for any state aspiring to real power in the Middle East. The Akkadian Empire was undone by a prolonged drought that overwhelmed its capacity to manage water and sustain agriculture. The Islamic Republic of Iran is no exception to this historical logic, for three reasons.

First, large-scale water management functions as a stress test for state capacity. In arid systems, irrigation, groundwater control, and urban supply require long planning horizons, stable institutions, and credible/transparent data. When authority fragments and technical decisions are subordinated to political signaling, environmental pressure compounds rather than dissipates.

Iran has reached that point. Years of fragmented governance, politicized dam construction, and opaque data practices have undermined the state’s capacity to manage scarcity.

In November 2025, after an extended drought forced rationing and prompted contingency planning around Tehran, authorities turned to cloud seeding operations near Lake Urmia. The decision was not significant for its likely hydrological impact, which is marginal at best, but for what it revealed. Crisis management had narrowed to symbolic, short-horizon interventions, standing in for structural correction.

Second, water management determines food security, which in turn constrains economic and political stability. Groundwater depletion in Iran—losing an estimated 5 billion cubic meters annually nationwide, with Tehran’s region irretrievably depleting 101 million m³ yearly—has reduced rural incomes, increased dependence on food imports, and fed inflationary pressures (food prices surging around 64% in late 2025) that the state struggles to contain under sanctions. Agriculture consumes over 90% of Iran’s water yet contributes only approximately 12% to GDP, amplifying waste and vulnerability as reservoirs reach historic lows (e.g., Tehran’s five main dams at 13% capacity in early 2025). Water failure thus migrates directly into macroeconomic vulnerability.

Third, hydraulic failure reshapes territorial control and long-term strategic depth. Persistent water scarcity drives internal displacement, hollows out peripheral regions, and concentrates populations in already overburdened urban centers. Over time, this distorts settlement patterns in ways that weaken the state’s ability to govern space evenly.

Iran has begun to acknowledge this reality indirectly. By late 2025, water shortages, land subsidence, and unsustainable consumption levels in Tehran had reached a scale that prompted the president to publicly raise the prospect of relocating the capital. The argument was framed in economic and environmental terms, but its strategic meaning was unmistakable. A state that contemplates abandoning its political center due to resource exhaustion is conceding that its territorial configuration has become unmanageable under existing institutional constraints.

The President of the Islamic Republic, Masoud Pezeshkian: "In Tehran, if we cannot manage and people do not cooperate in controlling consumption, there won't be any water in dams by September or October."

Moreover, the pressure is already visible beyond the capital. Chronic water stress in provinces such as Khuzestan, Isfahan, and Sistan-Baluchestan is eroding the regime’s capacity to project authority uniformly, accelerating internal migration while weakening control over frontier regions that anchor Iran’s strategic depth.

This is a significant and embarrassing strategic error. Khamenei failed to recognize the water crisis as a core governance problem. He did not treat it as a strategic priority, did not compel institutional corrective action, and did not hold the agencies responsible for the mismanagement accountable. As shortages deepened, senior officials have also misread the situation and were allowed to engage with conspiracy theories, blaming foreign plots for problems rooted in domestic neglect—for instance, state-aligned media and officials repeatedly accused neighbors like Turkey, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia of “diverting” or “stealing” rain clouds, while some claimed the United States and Israel were manipulating Iran’s clouds. This refusal to see the crisis clearly—and to act on it—allowed technical failure to metastasize into political paralysis.

2- Taking the Proxies for Granted

Khamenei treated Iran’s proxy network as a permanent asset rather than a contingent one. Hezbollah, Iraqi militias, and other aligned forces were assumed to be durable extensions of Iranian power, capable of absorbing pressure indefinitely without strategic recalibration from Tehran. This assumption ignored how attrition and battlefield adaptation steadily degraded their effectiveness—for instance, in the 2024–2025 Israel-Hezbollah conflict, Hezbollah suffered an estimated 4,000 fighter losses, the assassination of leader Hassan Nasrallah, and the destruction of much of its arsenal and infrastructure in southern Lebanon.

He also failed to recognize that proxies impose governance costs at home. Resources diverted to sustain external actors came at the expense of domestic investment, particularly under intensified sanctions that contributed to inflation, a rial devaluation to over 1,000,000 rials per dollar, and a sharp contraction of Iran’s middle class.

More importantly, as returns diminished and the fall of the Assad regime severed key supply lines, the Islamic Republic did not reassess its regional strategy but instead intensified it. The clerical security system is structurally incapable of strategic correction because it exists to preserve revolutionary orthodoxy. That orthodoxy is enforced internally through the Guardian Council’s gatekeeping and validated externally through proxy warfare as proof of ideological vitality. Since retreat would signal ideological failure, adjustment became impossible. The result was institutional lock-in, binding Iran to an increasingly costly regional posture even as its leverage steadily eroded.

This dynamic produced not only overextension but a deeper crisis of credibility within Iran’s proxy network. When Hezbollah came under sustained pressure and Tehran failed to intervene decisively, the deterrent logic that underpinned Iran’s regional strategy collapsed. Proxies that once relied on Iran’s willingness and capacity to escalate were forced to confront its limits, exposing the widening gap between revolutionary ambition and operational reality.

3- Misreading Israel’s Military Achievements

Khamenei consistently underestimates the learning curve and operational sophistication of Israel’s military.

Israeli campaigns demonstrated precision targeting, intelligence fusion, and escalation control that directly challenged Iran’s assumptions about survivability and response thresholds—for example, the targeted assassinations of senior IRGC commanders like Hossein Salami and Mohammad Bagheri, along with nuclear scientists, during the June 2025 strikes, and the achievement of air superiority over Iranian territory with over 200 aircraft striking more than 100 targets while suffering minimal losses.

Rather than updating doctrine after this utter humiliation, the Iranian leadership dismissed these outcomes as temporary or exaggerated, downplaying the destruction of key air defenses and the limited impact of Iran’s retaliatory missile barrages, most of which were intercepted. This refusal to absorb empirical evidence left Iran’s security institutions operating on outdated threat models, incapable of responding proportionately or credibly.

At this point, Khamenei’s judgment is distorted by one of two failures. Either information reaching him is filtered to protect ideological narratives rather than convey operational reality, or he is himself captive to a theology of jihad and martyrdom. In both cases, this produces a dysfunctional system and a pathological decision-making process.

4- Misreading President Trump and American Resolve

If there is one constant in Khamenei’s interaction with Washington, it is his repeated misreading of Trump.

More broadly, he has interpreted fluctuations in U.S. policy as evidence of strategic exhaustion rather than selective engagement. Decades of American willingness to reopen channels, absorb provocation, and accommodate the regime, even at the expense of allies such as Saudi Arabia and Israel, conditioned Tehran to treat de-escalation as the default outcome of pressure. That assumption no longer holds.

This misreading is especially acute under Donald Trump and takes three forms. First, Khamenei interprets Trump’s openness to negotiation as a reluctance to impose costs, rather than as leverage conditioned on enforcement. Years of U.S. accommodation, especially under Obama and Biden, conditioned Tehran to expect that “talks” would substitute for pressure. Under Trump, pressure is precisely the precondition for any “talk.”

Second, Khamenei conflates tactical volatility with strategic reversibility. Trump’s erratic style obscures an important fact: when he articulates red lines, he enforces them.

Third, Khamenei reads restraint as fear of escalation rather than credibility built through follow-through. This is most evident in his treatment of nuclear policy. He underestimates Trump’s opposition to nuclear proliferation, dismissing it as rhetorical positioning rather than as a core priority backed by sanctions, enforcement, and coercive pressure. The February 2025 restoration of maximum pressure aimed at driving oil exports to zero, paired with parallel signals of willingness to negotiate, was interpreted in Tehran as evidence of divisible Western resolve.

But more importantly, Khamenei repeats a pattern whose outcome is already visible. He has watched leaders such as Nicolás Maduro publicly mock Trump, dismiss enforcement signals, and treat deterrent warnings as performative, only to see defiance culminate in isolation and eventual capture.

Maduro’s televised challenge during U.S. military escalations ended not in leverage, but in removal. Khamenei now mirrors the same logic. He turns to social media to cast Trump as another fallen ruler and does not understand that “words” have consequences.

But this posture reflects a deeper blindness. Khamenei appears not to register the limits of external backing. Vladimir Putin did not shield Iran during Israel’s Operation Rising Lion, for two straightforward reasons. Russia lacks escalation dominance in the Middle East and avoids direct confrontation with Israel where it cannot control outcomes, and Putin has already demonstrated in Syria that he will not absorb costs to save exposed partners, having failed to prevent the collapse of Bashar al-Assad when the balance turned.

Xi Jinping is even less inclined to intervene. China prioritizes long-term economic access, energy security, and influence accumulation, not regime rescue under pressure, and it avoids entanglement in conflicts that threaten trade flows or invite confrontation with the United States. Iran is a supplier and a bargaining chip, not a commitment.

Khamenei mistakes Putin and Xi’s rhetorical alignment for strategic insurance. It is not.

5- Betting on China

Khamenei also overestimated what alignment with China could deliver under sanctions, misreading both Beijing’s incentives and its operating model. China’s engagement in the Middle East is driven by two primary objectives.

The first is energy security. Beijing seeks long-term access to oil and gas at predictable, discounted prices to sustain growth and hedge against disruptions to U.S.-controlled maritime routes. The second is strategic positioning. The region offers ports, logistics corridors, digital infrastructure, and diplomatic leverage that enable China to incrementally contest U.S. influence without direct confrontation. Iran fits neatly into this framework, but only as a means, not as an end.

Under sanctions, Tehran becomes a captive supplier. China absorbs Iranian oil at scale, nearly 90 % of exports in 2025, averaging 1.5 to 1.8 million barrels per day, while imposing steep discounts of $5 to more than $10 per barrel to price in sanctions risk. Payments are structured through opaque channels, barter arrangements, or delayed settlement, minimizing Chinese exposure while locking Iran into dependence. This secures energy flows for Beijing while shifting risk entirely onto Tehran.

The 2021 25-year cooperation agreement operates on this basis. It grants Beijing flexibility without a binding commitment. Projects advance selectively, capital deployment remains cautious, and technology transfers are confined to non-sensitive areas. Earlier strategic assistance, including support that helped Iran sustain ballistic missile capabilities, already achieved China’s immediate objectives by complicating U.S. regional dominance. Beyond that point, Beijing avoids entanglement, as I stated earlier, to avoid inviting secondary sanctions or linking it to Iran’s internal instability.

The result is a one-sided relationship in which Iran absorbs risk while China extracts advantage. Years of operating under isolation have conditioned Khamenei to equate endurance with autonomy, blinding him to the dependencies that isolation itself has produced.

This pattern is historically familiar. During the late Cold War, regimes aligned with the Soviet Union, such as Afghanistan under Najibullah or several Eastern European client states, mistook external backing for strategic independence. Moscow sustained them selectively, but once costs rose or priorities shifted, support thinned, and structural weaknesses were exposed.

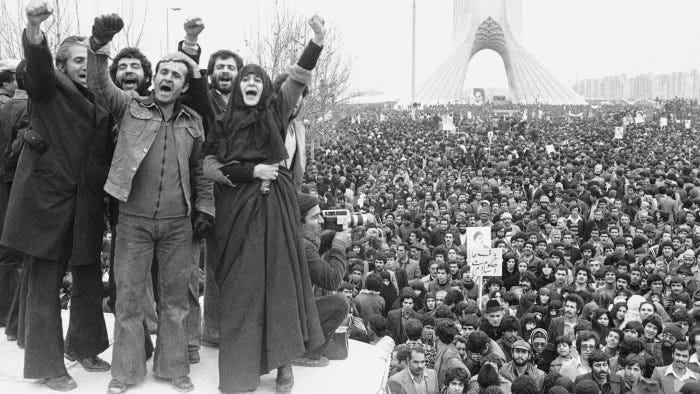

6- Alienating the Next Generation

Khamenei failed (and still fails) to grasp the depth of generational rupture inside Iran.

Younger Iranians are being treated as ideologically recoverable rather than structurally alienated, even as their expectations are being shaped by global connectivity and regional comparison, with over 40% of the population under 25 facing youth unemployment rates around 20-23% (and up to 35% for young women), Khamenei lives in a parallel universe where his calls for Jihad are appealing.

In revolutionary regimes, youth are not peripheral, they are the regime’s core claim to legitimacy and renewal. The Islamic Republic itself is a product of youth mobilization. In 1979, students and young clerics formed the backbone of street organization and ideological dissemination during the Iranian Revolution. In the 1980s, the regime institutionalized that energy through the Basij, embedding revolutionary loyalty across neighborhoods, schools, and different military units.

That model is now failing for two reasons.

First, indoctrination no longer translates into belief because lived reality persistently falsifies revolutionary claims. Economic exclusion, social restriction, and prolonged stagnation have degraded the regime’s claims to justice and moral purpose, converting ideology from an asset into a structural weakness.

Second, the regime has shifted its reliance toward coercive enforcement as a substitute for consent, a dynamic that sanctions have intensified by compressing domestic economic horizons at the precise moment regional peers were expanding theirs. The contrast with the UAE and Saudi Arabia’s diversification through tourism, capital inflows, and investment has further delegitimized the Islamic Republic’s governing model.

Khamenei invested heavily in expanding external proxies while neglecting the domestic generation meant to sustain the system that produces them. The regime exported revolutionary energy abroad but failed to nourish it at home. Proxies require a continuous supply of belief, manpower, and legitimacy. When the youth disengage, the revolutionary engine collapses.

7- Overestimating the Coercive State

Khamenei continues to operate on the assumption that coercion, supplemented by illicit finance and sanctions evasion, can substitute for governance. Security forces are deployed to address economic and demographic problems, not political ones. That trade-off does not hold, since policing dissent suppresses visible unrest while leaving the underlying drivers of unrest intact.

To be more precise, the system assumes force can be sustained indefinitely. But it obviously cannot, as sanctions enforcement tightens, shadow banking, informal trade, and proxy-mediated revenue streams narrow and become harder to scale. U.S. measures targeting dozens of entities and vessels involved in Iranian oil exports further constrained illicit channels. The result is revenue volatility inside the coercive apparatus itself. Loyalty becomes conditional, tied to pay and protection rather than ideology, even as the 2025 budget expands military spending by roughly 200%, to more than $12 billion, amid growing fiscal strain.

The more the system relies on force, the more visible its inability to govern becomes. Khamenei’s institutions, designed for control, are being stretched into roles they cannot fulfill.

Conclusion

What distinguishes the present moment from earlier crises is not simply the scale of unrest but the absence of usable exits. In the past, the regime could recalibrate through repression, external mediation, regional escalation, or economic relief. Those options are now either blocked or counterproductive.

Khamenei’s decisive failure is therefore not miscalculation alone but the refusal to learn. He continues to interpret pressure through assumptions formed under earlier U.S. administrations, underestimating how enforcement has changed under Donald Trump.

Indeed, for decades, the regime survived by exploiting hesitation and waiting out constraints, assuming pressure was episodic, negotiable, and reversible, an assumption that shaped both its regional posture and its internal control. That logic has collapsed. Red lines are enforced, sanctions are sustained, and deterrence now operates through action rather than rhetoric, yet Khamenei continues to misread this shift as temporary rather than structural. Each act of defiance, therefore, intensifies pressure instead of dissipating it, leaving a system that can still wield force but can no longer regenerate belief, sustain loyalty, or restore strategic balance, a condition this crisis is unlikely to allow it to survive.

This is superb. Not a word wasted.

A brilliant write up. Thanks very much.

The 1979 Islamic revolution and ousting of Shah was engineered by bazaar, clerics and the people. This one also started from the bazaar but without clerical support. 3.4 million small and medium businesses are hurt by couple of major financial-military giants who don’t let anyone else to take a share of the economy. As such the structure has changed.

You made important analysis in yours.

Thanks very much.