Why American Power Is Always on Trial

Guilty for Acting

“War is the most painful act of subjection to the laws of God that can be required of the human will.” Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace

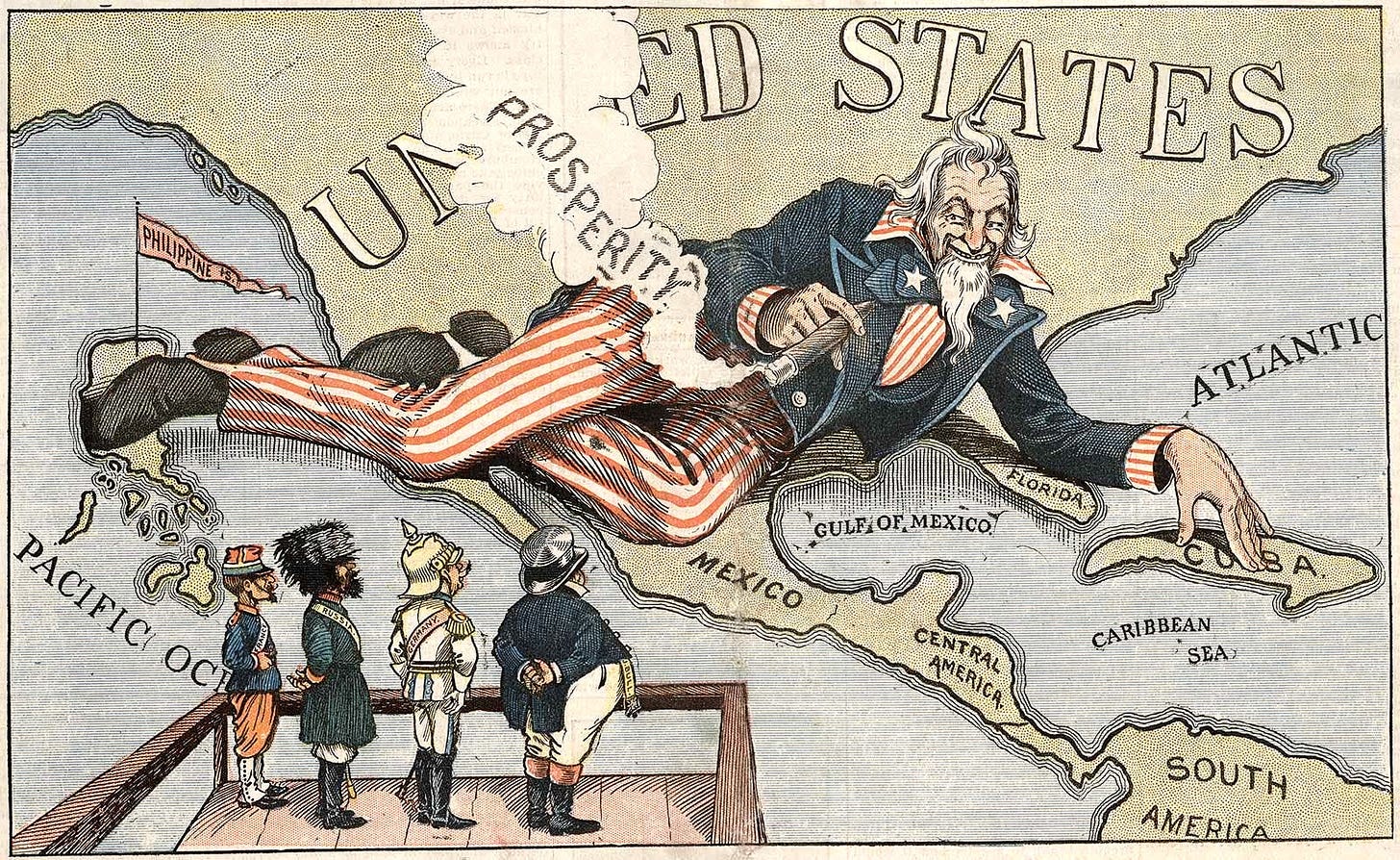

Whenever the United States moves, the verdict is already in. Action itself is treated as a provocation. Whether Washington intervenes militarily, applies economic pressure, recognizes an opposition movement, or enforces its laws beyond its borders, the response follows a very familiar script. The act is declared illegitimate, unlawful, or immoral, often all at once. This reflex has become so ingrained that it no longer operates as criticism of specific decisions, but as a standing assumption about American power. The problem is not what the United States does. It is that it does anything at all.

This reflexive contestation was on full display following Operation Absolute Resolve. On January 3, after months of escalating pressure that included maritime interdictions, a naval blockade involving some 12,000 personnel aboard nearly a dozen warships, and the arrival of the USS Gerald R. Ford carrier strike group in November 2025, the United States executed a complex military operation that resulted in the capture of Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores.

Both were transferred to the United States to face trial on narco-terrorism charges filed initially in March 2020. From Washington's perspective, the operation was the culmination of a long-standing legal and strategic position. The United States had never recognized Maduro as Venezuela's legitimate president, and it had indicted him for leading the Cartel de los Soles, an organization accused of trafficking between 200 and 250 metric tons of cocaine annually through Venezuelan territory.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio reiterated this position publicly, stating that Maduro was not the president of Venezuela, that his regime did not constitute a legitimate government, and that he functioned as the head of a criminal organization that had seized control of a country. This assessment was not uniquely American. Following the disputed July 2024 election, more than 50 countries, including the European Parliament and numerous Latin American states, recognized opposition candidate Edmundo González as the rightful winner.

And yet, despite the regime’s criminal character, its collapse of state institutions, and the mass displacement of Venezuelans across the hemisphere, the dominant international reaction focused not on Maduro’s illegitimacy but on the alleged illegality of American action.

The Decolonial Moral Framework

This reaction, however, cannot be reduced to a dispute over mere legal interpretation, it in fact reflects the convergence of two deeper frameworks that now structure much of global discourse.

The first is a decolonial moral lens that regards Western power, especially American power, as illegitimate by definition.

The decolonial intellectual tradition frames the United States through a moral genealogy rooted in twentieth-century anti-colonial and third-worldist thought. Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth casts colonialism as a total structure of domination, one that shaped not only material conditions but “consciousness” itself and one that could not be reformed from within. Later decolonial thinkers extended this insight beyond politics into law and international order. Walter Mignolo extends this idea, arguing that modernity and coloniality emerged together, that the universal language of reason, legality, and progress was forged alongside empire and continues to bear its imprint. Aníbal Quijano’s concept of the “coloniality of power” similarly holds that hierarchy did not disappear with “formal decolonization” (states declaring independence from colonial powers) but persisted through institutions and norms that organize the modern world. Within this framework, the United States is not evaluated as a particular state making choices under constraints, but as the most complete expression of a colonial, oppressive, and “morally evil” system whose legitimacy is already dismissed.

What is interesting here is that this ideology reshapes how international law is interpreted when applied to American action. Law is not seen as a mechanism that imperfectly but meaningfully constrains power, it is seen instead as a language through which domination presents itself as “universality”. Institutions such as the United Nations, international courts, and even the concept of sovereignty are read as extensions of Western hierarchy maintained through procedure rather than force. When the United States invokes international law, it is therefore assumed to be exploiting legality rather than submitting to it. Even legal action against manifestly criminal regimes is absorbed into a narrative of domination imposed on the Global South.

There are, of course, two fundamental contradictions in this way of thinking.

The first contradiction concerns the law. The decolonial view insists that international law is illegitimate because it emerged from colonial power, but somehow remains authoritative enough to sit in judgment of the United States. The law is dismissed as corrupt in origin, but treated as unimpeachable in application, provided it is being used to restrain American action.

The second contradiction is about power. This view treats power itself as abusive, despite its dependence on American power to keep the international system from collapsing. It calls for restraint from the United States while offering no real alternative for enforcing order, protecting civilians, or stopping predatory regimes. The desire to limit power is confused with the belief that order can exist without it.

This is also why the United States is often perceived as evil. Because American power “supports” the current international system, it becomes the easiest target for everything people dislike about that system. Inequality, historical grievances, and present failures are all blamed on the United States, regardless of who caused them. America is judged less by what it actually is or does than by what the world it helps sustain is accused of being.

The third contradiction is political alignment. Decolonial thinking presents itself as a critique of domination, even though it often centers on states and movements defined primarily by their opposition to the United States. Regime character becomes secondary to geopolitical posture. Authoritarianism, repression, corruption, and even imperial behavior are excused or minimized so long as they are directed against American power. States are judged not by how they govern, but by whom they oppose. This produces a curious reversal. Anti-American regimes are treated as agents of resistance regardless of their conduct, while American action is treated as suspect, evil, and ignorant, irrespective of its purpose.

The Post-1945 Legal European Mind

The second framework shaping these reactions is doctrinal, rooted in Europe’s post-1945 legal order and its distinctive understanding of legitimacy. European interpretations of international law, particularly under the UN Charter, prioritize non-intervention and procedural authorization over all other considerations.

The use of force is considered lawful only when it satisfies a narrow set of formal conditions, most notably explicit Security Council authorization or a strictly reactive form of self-defense. Action that precedes authorization, even when intended to prevent state collapse, transnational criminality, or large-scale harm, is viewed with deep suspicion.

Europe’s historical experience with discretionary power left a deep imprint. Appeals to necessity and anticipation had too often been used to justify catastrophe. After two world wars, restraint was elevated into a principle. Legality came to signify the curbing of initiative rather than the management of emerging threats, a preference that gradually solidified into doctrine.

Two additional dynamics help explain why this very doctrine produces such consistent skepticism (and I should say visceral hatred, too) toward American action.

The first is Europe’s postwar delegation of hard security to the United States. For decades, American power absorbed the costs and risks of deterrence, escalation, and enforcement, while European states focused on integration, law, and institutional governance. This division of labor gradually transformed legal restraint into a moral identity. Because Europe was rarely required to act decisively, legality could be treated as an absolute rather than as a tool tested under pressure. American action, by contrast, came to appear destabilizing precisely because it exposed the gap between legal ideals and the realities of enforcement that Europe itself no longer confronted.

The second problem is institutional paralysis. European legal thought places considerable faith in multilateral institutions, particularly the United Nations, as the primary source of legitimacy. In theory, action is considered lawful only when these bodies approve it. In practice, however, they are slow, vetoed, and often unable to respond when crises involve powerful states or criminal regimes.

Instead of confronting this reality, the standard response is to lower the definition of legitimacy. If “legal authorization” cannot be obtained, then the action itself is declared illegitimate. The system's failure is not acknowledged but shifted onto the actor willing to act, typically the United States.

As a result, American actions are often judged less by what they aim to achieve or by whether they work, and more by whether the correct procedures were followed. When authorization is missing, that absence matters more than the threat itself. In this view, any American initiative disrupts order.

This logic leads to a very basic analytical error. By equating American enforcement actions with Russia’s invasion of Crimea, European legal reasoning reverses essential distinctions. It treats fundamentally different uses of power as if they belonged to the same category. Enforcement aimed at constraining disorder is analyzed in the same terms as territorial conquest, designed to revise borders. In doing so, it inverts cause and effect, turning restraint into instability and aggression into equivalence.

Russia’s seizure of Crimea was an act of territorial conquest aimed at permanent annexation and border revision. It explicitly rejected the postwar European order and sought strategic expansion through force. American actions of the kind under discussion operate in a different register. They are limited and oriented toward enforcement rather than acquisition. Treating both as equivalent strips “international law” of its own ability to distinguish between conquest and constraint.

The same misreading lies behind the claim that American action emboldens China to move against Taiwan. This argument assumes that major powers take their cues from legal precedent. In reality, they respond to strength, resolve, and capability. Beijing’s calculations are shaped by U.S. military posture, alliance cohesion, industrial capacity, and political will, not by procedural debates over authorization in distant and unrelated cases. Legal processes do not deter authoritarian states, only military power does. When American restraint becomes habitual, it does not reinforce norms, it communicates uncertainty about whether the United States is prepared to act when those norms are challenged.

The “America is Bad” Loop

These two habits of mind now meet seamlessly in public discourse. Decolonial thinking is absorbed early, taught in classrooms and lecture halls where American power is introduced less as a historical actor than as a moral problem. By the time students graduate into newsrooms, NGOs, and policy circles, suspicion of U.S. action no longer needs to be argued. It is already part of the air. European legalism then supplies the idiom. Non-intervention and procedural breach become the polished terms through which that suspicion is expressed.

Venezuela exposes the pattern. International law was used to shield a narco-state that dismantled democratic institutions, trafficked drugs, and weaponized migration. The choice of Venezuelan voters, reflected in an election the opposition won decisively, was ignored. Under this logic, American inaction would have counted as legality, even if it meant letting a criminal regime remain in power, flood American streets with drugs, and drive thousands more into exile each day.

A refreshing, thorough analysis of current international political thinking. Instead of simply reciting the protestations of the Left, the article examines the Left’s underlying assumptions. Why does it go so far as to support a tyrannical military regime that seizes power by blatantly subverting a democratic election, raises money by drug trafficking, allies with other tyrannical regimes (Iran and China), and destroys a formerly vibrant economy? In short, because it reviles and rejects any assertion of US power — even in the Western hemisphere. And why is that? For the reasons set forth in this piece. This is a lucid explanation of the strange positions and presuppositions of the Left today. An explanation sorely needed to understand our world.

Excellent essay!