The Logic of Third-Worldism

The New Face of Political Mobilization

“If you want to make use of the advantages of civilization, but are not prepared to concern yourself with the upholding of civilization, you are done.”

― José Ortega y Gasset, The Revolt of the Masses

General Observation: Israel, the Left, and the Masses

I have been following the rise of “Your Party” in Britain like everyone else. I watched the speeches of Jeremy Corbyn, Zarah Sultana, and their comrades, and I kept thinking that something deeper was taking shape. I don’t think it’s coordination, but a form of cross-pollination. There is a circulation of ideas, a movement of currents across the Atlantic, and the Western Left is absorbing them in parallel.

I have argued about this with friends. Some believe that I overestimate the return of Third-Worldism as an ideology, and they insist that voters care about material issues such as wages, jobs, and housing. They are not wrong. Material precarity is real, it becomes politically dangerous when inequality remains unaddressed, and a nation should worry when its young cannot work, cannot form families, and cannot plan for their future. However, however, however, and however, the political energy that is now forming is not purely economic. It blends genuine social grievances with an ideological reflex rooted in post-colonial and anti-imperial narratives.

This matters for anyone working in foreign policy. Mass movements often reshape the strategic environment long before institutions notice. Public moods travel across borders, and narratives migrate faster than officials can respond. Foreign policy is forced to operate inside a new cultural atmosphere that emerges from social perception rather than elite decision-making.

Ortega y Gasset helps clarify what is unfolding. His revolt against the masses was not about class conflict but about a psychological orientation seeking a permanent sense of historical mission. This is precisely the structure that animates most populist movements, but even more so the contemporary Western Left. Social democrats can govern through economic policy, but that technocratic mode does not generate the symbolic energy needed to sustain a movement. The activist Left, therefore, seeks a new revolutionary cause.

This is why the post–October 7 moment has been so significant. The anti-Israel mobilization has given the contemporary Left a fresh revolution. It provides a straightforward narrative and a sense of participating in a global struggle, which restores the immediacy and certainty that Ortega described.

I joked on X that CBS tried to set up a debate between Ben Shapiro and Hasan Piker on capitalism, and Hasan reportedly refused unless the topic became Israel. The episode looks absurd, but for many activists, Israel is not a separate issue. It has become the central lens through which economic critiques are interpreted. It is, in fact, the narrative par excellence that anchors their worldview.

The Logic of Third-Worldism

As I said before, the contemporary Left is being absorbed by a new wave of Third-Worldism that treats anti-Israel politics as the core axis of moral meaning. Gaza has become the central symbol because it fuses every theme the activist Left needs: victimhood, colonial injustice, racial hierarchy, and global resistance. This is why figures like Greta Thunberg shifted from climate justice to Gaza without hesitation. Climate politics offered urgency but not a revolutionary antagonist. Gaza provides both.

Jeremy Corbyn’s return through “Your Party” also makes this shift unmistakable. He appears vindicated because the worldview he always represented has moved from the margins to the emotional core of the Western Left.

Britain and the United States, despite their differences, show the same dynamic. Both cultures carry a frontier spirit and impulse, a desire for moral purpose and transformative struggle, and contemporary Third-Worldism channels that impulse differently by offering a global narrative of oppressor and oppressed. Traditional social-democratic politics, which depends on institutional work and economic programs, cannot compete with that kind of moral immediacy. What rises in its place is a movement drawn toward distant conflicts that promise symbolic redemption.

But at the end of the day, the transformation is not essentially about Israel. It is about identity. The Left is rebuilding its sense of self around moral purity, a very common theme. Gaza becomes the arena where this identity is enacted and affirmed. Class politics and policy commitments demand continuity and discipline, but identification with global victims delivers instant “meaning” or “sense of history”.

In Europe, where the political tradition differs from the United States and the American Right still carries its own sense of historical revolt, the deeper force animating the Left is its persistent need for a cause that promises transformation. Marcuse already saw that once the Western working class ceased to be the historical agent of change, the revolutionary imagination would migrate toward groups and struggles outside the West. Anti-colonial movements, students, and racial minorities became the new carriers of world-historical meaning. That trend continues today. When domestic politics feels exhausted, the Left looks outward for a struggle that can restore transcendence.

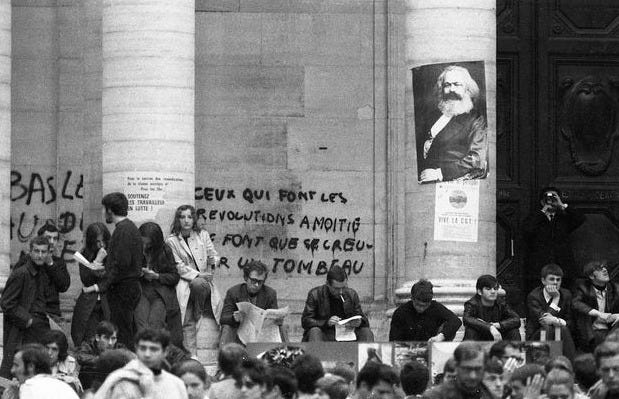

This pattern has deep historical roots. Figures such as Ho Chi Minh, Messali Hadj, and Nguyen An Ninh were radicalized not in Hanoi, Algiers, or Saigon but in Paris, where they entered a revolutionary milieu. The French Communist Party and its orbiting organizations reframed global liberation as an extension of European ideological battles, turning anti-imperialism into a reflective surface for Western moral aspiration. But this is where I see the significant and great rupture, it is one thing for anticolonial leaders to fight for independence within their own historical conditions, and quite another for Western activists to adopt those struggles as lenses through which they interpret their own societies. In the former case, grievance arises from lived experience and political necessity. In the latter, it becomes a way of reimagining the West from within, using foreign conflicts to supply meaning where domestic political narratives have faded.

The logic of Third-Worldism is then to lift an external struggle out of its own setting and elevate it into the central source of political purpose. The distant battlefield becomes a metaphysical stage where the self is purified. This allows the Western activist to assume the posture of righteous witness while remaining detached from the institutional, economic, and cultural demands that anchor political responsibility in their own world.

And this is precisely why my friends are mistaken when they argue that precarity is the true engine of the movement, because economic anxiety may set the mood and the environment, but it cannot generate this metaphysical search for purity or explain why distant struggles now carry more emotional weight.

The people with glaring personality disorders had to go somewhere, after wokism collapsed. Politics and trying to control the world is a normal place for people with extremely defective psychology. The problem for them though is that they're all the worst people and therefore can only work each other up into ever greater stupidity amd hysteria and sideline themselves eventually into being no more than irrelevant public nuisance again. Third worldism is merely a movement of individual dysfunction that will gain some power by terrifying the normies for a while, but collectives of Cluster Bs will never build anything true or good.

Yes, "symbolic redemption" is the name of the game and there couldn't be two better candidates to supply it.

The Palestinians, a Western fetish object for the past half century, whose narrative of heroic rebels fighting for freedom and justice against colonial imperialism was crafted by the Soviet Union—and like so many spawns of the Soviets, what for them was a cynical strategy for power became holy writ for their Western academic epigones, who never met a radical pose they didn't like, esp if it meant they could stay safe on campus getting checks and tenure while other people bled and died for their status games and fantasies of leading revolutions. This is why every Palestinian grievance is confirmed and sanctified, why their every wound and calorie is detailed and tallied and every massacre they commit is reframed as a righteous battle against Oppression—Communism is a proxy Christianity with Karl as its prophet and capitalism as its Satan and the Palestinians are now the Communist Christ, the sacred spotless victim at the center of their moral universe, the savior we must bleed, kill and die for.

And against them is Israel with its sins of continuing to exist and refusing to be erased, currently being transformed into the newest iteration of the ancient Jewish scapegoat. (The Jewish scapegoat gets loaded with all the supposed crimes and neuroses of each age, as assigned by various moral, political, and ideological entrepreneurs. One generation they're too foreign, then they're too ubiquitous; then they're too capitalist, then they're too communist; then they're too weak and bookish, then they're too martial and aggressive etc etc.) Now the jargon-crafting moral bullies of Left Academia are the ones who get to create and desseminate the new list of crimes to be loaded atop the Jewish scapegoat: settler-colonial white-supremacist imperialist ethnostate apartheid genocide etc. And turning Israel into a pariah state and ultimately destroying it is the goal with "symbolic redemption" the reward.

Jew hate is back in style, which usually means that what comes next are marches denouncing Jews (uh, I mean "Israel"), pogroms, political extremism, conspiracy theories, fights in the street, social unraveling—we've checked a few of those boxes already.

After a few decades asleep and narcotized by cash and clicks, History is back!

Thanks for the great work...