MBS, the Saudi Revolution, and Saudi Futurism

The Great Shift

“You ask me whether the Orient is up to what I imagined it to be. Yes, it is; and more than that, it extends far beyond the narrow idea I had of it.”

Gustave Flaubert

Understanding Saudi Arabia Today

This week in Washington was unusually revealing. Saudi Arabia dominated the conversation, and the meeting between MBS and Trump naturally became the focal point. But the analysts were caught in old patterns, more absorbed in what Saudi Arabia could eventually deliver than in what it is already driving forward.

For years, the conversation about Saudis in Washington has been filtered through a narrow set of issues, mainly Khashoggi, human-rights criticism, and oil politics. But now that Riyadh is back at the center of strategic discussions, commentary is, as always, divided: some critiques are valid, others miss the country's orientation entirely.

I have never visited the kingdom, but like anyone from the region, I feel its gravitational pull. Its choices shape political, economic, and cultural dynamics across the Middle East. Saudi Arabia’s internal logic, however, remains the most overlooked part of the story.

Indeed, Saudi Arabia emerged from a distinctive fusion of tribal authority, religious doctrine, and resource wealth. The alliance between the House of Saud and the Wahhabi establishment, formed in the 18th century, brought cohesion to a landscape otherwise defined by atomization. The clerical class provided religious legitimacy, but it also limited social development and institutional flexibility.

By the early 21st century, this entire structure was carrying more weight than it could reasonably support. The population grew rapidly, cities expanded at a remarkable pace, and global economic integration raised expectations that the older system could not meet.

When I look at Saudi Arabia today, at the cultural festivals, the biennials, the opening of public life, I see a country trying to step out of that inherited rigidity. This is where, in my view, Mohammed bin Salman made a clear judgment: that a religious doctrine designed for the social world of the 18th century cannot sustain a country of more than 35 million people living in large metropolitan areas and remaining connected to the outside world.

Clerics once shaped education, entertainment, and public behavior, and their influence fixed the limits of what could be imagined. Logically, society cannot adapt when inherited certainties narrow its sense of possibility. From what I can tell, MBS reduced that authority and reorganized the religious sphere so that the state, rather than the clerical hierarchy, could guide cultural life, public norms, and, more importantly, national identity.

This matters for regional politics. The Middle East has long engaged in an intellectual struggle with modernity. Thinkers such as Muhammad Abduh and Ali Abdel Raziq described the region’s difficulty integrating scientific advancement, state rationalization, and religious authority into one coherent framework. The inability to resolve this tension created cyclical crises. Societies gained literacy, education, and urban life, but the institutional and religious structures needed to channel these forces stalled. The result, as one can see in contemporary Middle Eastern history, is intense frustration and ideological extremism.

In a certain way, Iran developed one of the most explicit expressions of this conflict. The Islamic Republic’s ruling elites draw from a tradition that views Western influence as a corrosive force. Jalal Al-e-Ahmad described this in his concept of Gharbzadegi (Occidentalitis), which he defined as an intoxication by the West that dissolves a society’s inner substance. Ali Shariati expanded this idea by linking Islamic revivalism to anti-imperial struggle.

The current Iranian leadership still depends on these foundations. It presents Western modernity as something that empties a community of its soul and leaves it dependent on foreign technology. This narrative justifies strict clerical oversight of education, culture, national identity, and, of course, the different forms of political expression.

“I say Occidentalitis like one says cholera. But no. It is at least as serious as sawfly larvae in wheat fields. Have you ever seen how they infect wheat? From the inside. There is a healthy skin on the surface, but it is just a skin, exactly like a cicada’s shell on a tree.” Jalal Al-e-Ahmad

Saudi Arabia under MBS offers the opposite answer to the same civilizational question. For more than a century, Muslim thinkers have argued over whether modernity undermines a society or reinforces it. Iran does not reject technology entirely, the Islamic Republic builds missiles, drones, and cyber capabilities. But it does so inside a worldview that treats Western modernity as spiritually corrosive. Technology is tolerated only as an instrument of permanent confrontation with the outside world, not as a tool for strengthening social, institutional, or economic life at home.

Saudi Arabia follows a different logic. It treats modernity not as a danger to be contained but as a strategic resource to be mastered. Scientific progress and technological adoption are viewed as national assets. This shift creates space for modern institutions to gain legitimacy and places religious identity within a broader civic framework. In Saudi history, that alone is a revolution.

I do not know MBS, I have never met him, and I cannot pretend to know what is in his mind. But it seems to me that he is betting on a specific direction. The course he sets on technology, investment, and cooperation with Western partners, combined with the kingdom’s position as guardian of Islam’s holiest sites, is meant to redefine the region’s political and religious landscape. He is positioning Saudi Arabia to determine what a modern Sunni Muslim power can be, and that choice will shape the region for decades.

The Role of Futurism

In general, I would say that “Futurism” in politics serves several functions. First, it creates a new horizon of ambition, giving a society a sense of direction, a real orientation. Second, it breaks the grip of inherited religious or ideological assumptions about what a country is allowed to become. Third, it defines the long-term strategic destination toward which the state must move. Fourth, it forces the bureaucracy to acquire the capabilities required by this destination or strategic goal. Peter Drucker often argued that the real task of leadership is to prepare institutions for the world that is coming, not the world that already exists. MBS’s projects in Saudi Arabia are the clearest expression of these functions.

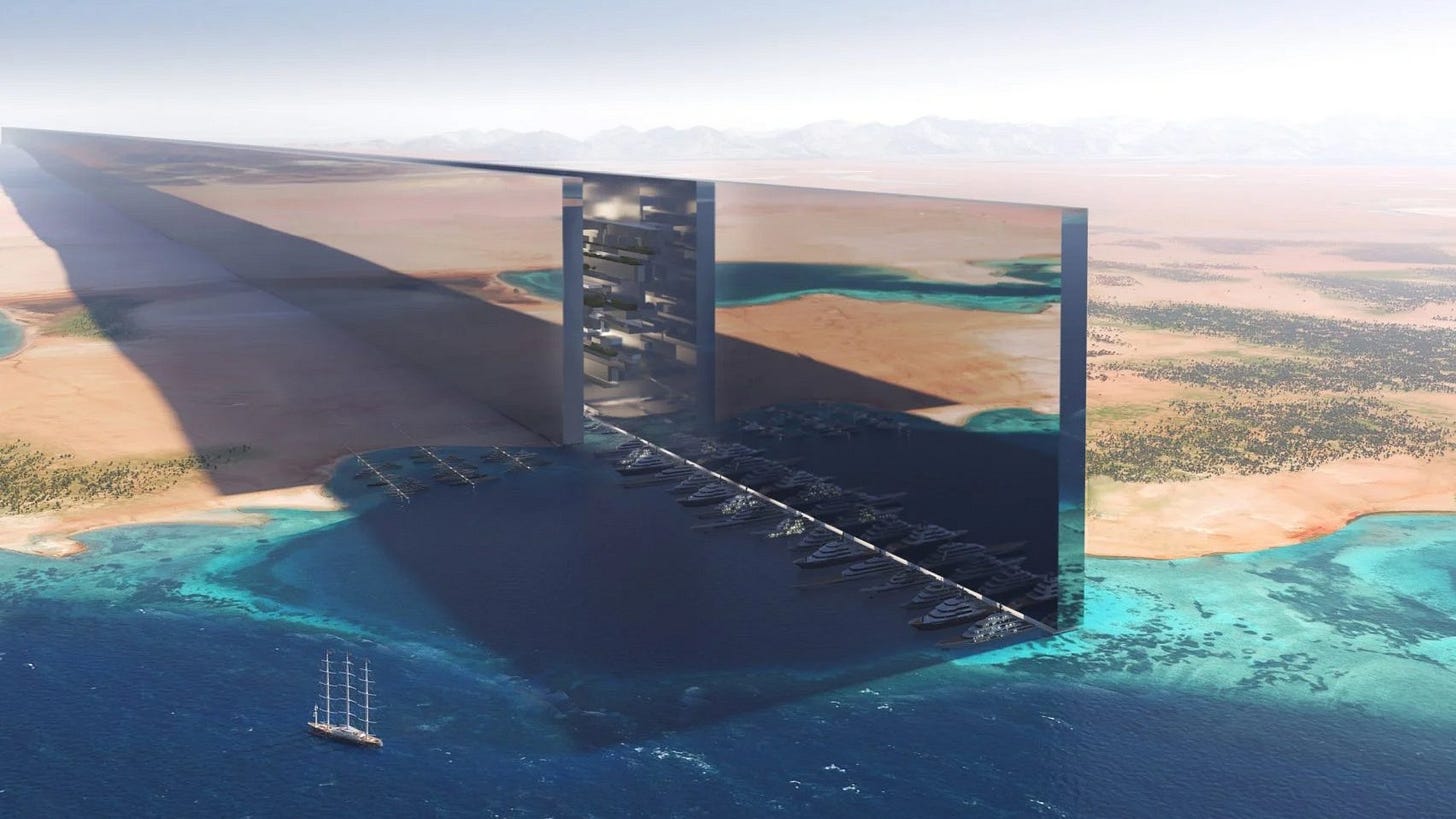

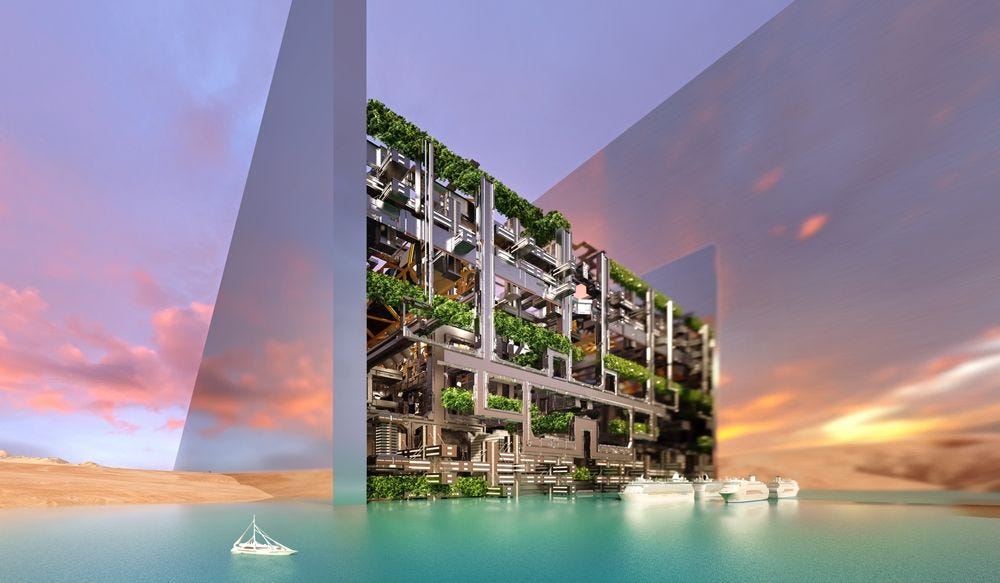

Projects like Neom bring together renewable energy research, autonomous mobility, biotechnology, advanced manufacturing, and experimental governance. From the outside, it can sound fantastical and absurd, and critics tend to fixate on delays and cost overruns as if Neom were simply an oversized real estate venture. That interpretation misses the underlying purpose.

Neom is, in fact, a long-term Saudi institutional laboratory. It obliges ministries, regulators, engineers, and private partners to work in an environment shaped by global standards and rapid technological change. The aim is to train the Saudi state to manage the sectors that define the 21st century. The outcome depends on the direction of institutional learning.

The Line project illustrates the same point. Many observers fixate on measurements, housing projections, and engineering constraints. They ask whether the structure will reach its originally announced length or whether the design will evolve. These questions matter for planners, but they miss the strategic and political function. The project fosters a mindset in which concentrated urban design and digital planning become part of the national conversation. Saudi society becomes accustomed to thinking about cities, infrastructure, and environment at a global scale. This cultural change carries more significance than any single architectural or financial component.

MBS’ futurism, therefore, serves a real and significantly underestimated political function. The country’s wealth gives the state room to pursue large-scale transformation, the monarchical structure allows decisions to be imposed without the paralysis of coalition politics, and this very combination enables futurism to operate as a genuine strategy for reshaping institutions and national identity rather than merely as a slogan. Few leaders have stated this purpose as openly as MBS.

On Religion and Identity

I think that the theological dimension remains central, but MBS’s futurism is reshaping it through economic pressure rather than religious debate.

For what functions as the Middle East’s equivalent of the Vatican, the implications are significant. State-driven modernization is altering the foundations of religious authority. Influence comes from the ability to operate within a rapidly expanding economic and institutional environment. Clerics who want to remain relevant must adapt to this new reality.

At the same time, the futurist projects create a momentum that leaves little room for clerical resistance. The speed of construction, the scale of investment, and the rise of new industries generate an economic force that overwhelms doctrinal objections. The pressure is not ideological, it comes from jobs, salaries, contracts and institutional incentives. This helps explain why the transformation of Saudi Arabia proceeds without large public religious confrontation, so far.

What Matters

Critics often miss the meaning of these developments because they judge them by short-term feasibility and lose sight of what is actually happening inside the country. The average Saudi today is not debating whether wearing a shirt is forbidden or whether looking at a woman will result in a thousand slaps. He is thinking about how to make his country stronger, what kinds of companies the economy needs, how to use the Red Sea as a strategic asset, and how Saudi Arabia can project power in the region. The state is reorganizing its institutions around innovation, educating citizens for global competition, and advancing a form of Sunni Muslim modernity that draws strength from regional influences.

Will the projects succeed? Will MBS succeed? I am not sure these are the right questions. It is true that Saudi Arabia cannot innovate at the pace of global leaders without deep human-capital development, and that such development takes decades to mature. But focusing on this misses the point. You cannot build a culture of innovation when innovation itself is not culturally valued. You cannot create world-class human capital when the public conversation avoids the very idea of it. MBS is targeting the structural obstacle that precedes everything else: the cultural lens through which Saudis understand ambition, modernity, and national purpose.

Saudi Arabia is now undergoing a transformation with regional implications. A country once associated with rigid conservatism is beginning to project confidence, openness, and strategic intent. The monarchy is using this shift to redefine its role in the Middle East. Observers who track construction timelines or budget forecasts rarely see the deeper tectonic movement taking place.

It is fascinating to watch the rapid technological changes that are occurring worldwide. The first question, always, is the old Western question of stability. Can those old 18th century Islamic elements be satisfactorily wedded to a high-tech society where human capital is truly developed? Famously, countries outside the First World have suffered revolutions and upheavals when they are on the brink of First World status. Cuba was the most successful Latin American country with the fastest rise in living standards when Castro took over and destroyed the country. Iran was making astonishing progress when revolution interrupted its course. Venezuela also succumbed after the same fashion. The revolution that Marx predicted for the advanced countries occurred in Russia and China — outside the West. Why? Indeed, there was something special about the West that protected the West, that allowed for freedom and development and more. An Islamist might say that the West is rotten, decadent, corrupt, soulless, etc. But such assessments are simplistic. The West is many things at once. There are so many cultural and intellectual moving parts that we cannot easily say what the West is. There is bad and good mixed together. How do we sort and analyze the elements? As it happens, there are a couple of people whose “thoughts” (or thoughts attributed to them) made the West into something different: Socrates and Christ. Neither of them wrote books, by the way; but most books written after them, possessing any importance, were influenced by their followers. What made Socrates and Christ important? The idea of truth and truthfulness, above all — even to the disadvantage of tradition (the Vatican), or religious belief, or political authority. Institutions are famously untruthful and must be corrected for progress to occur (if we should even believe in progress). But how is it possible in any sense? Truth in this sense is only possible if you have martyrs to the truth, which Socrates and Christ exemplified. Here we have an ultimate kind of authority, personified in humble form, being executed unjustly. Certain ideals and ideas are here contained. Improbable ideas, to be sure. One might argue that the roots of these ideas have been partly pulled up in the West — yet they have always been but a light seasoning. The margin of effect may be small, but nonetheless decisive. In fact, without a certain residue of Socrates and Christ in mix you end up with establishments like those in China and Russia — autocratic criminal regimes. The question for you is: What does the Saudi Kingdom have that could make a real difference in the larger struggle that is unfolding between West and East? Do the Saudis have Freedom? Philosophy? Goodness? Justice? — stability? Or will the Kingdom follow the path of Cuba and Iran?

What would change if MBS died suddenly? Is the power structure and intellectual capital such that his program could or would continue without him?